A beacon of light

More than 250 children living in poverty have witnessed a powerful holistic transformation since their local Compassion centre opened its doors. Now, the lives of a new generation are being transformed! Read more open_in_new

Hi, neighbour! We’re refreshing our site to make your visit better. As you move around, you may see a mix of old and new designs.

Compassion Honduras has a slogan: changing generations. “There is only one way we can do that, and that is addressing the coming generation,” explains Armin, a Compassion Partnership Preparation Specialist in Honduras.

Breaking generational cycles of poverty in Honduras is greatly needed—almost half the nation’s population live in poverty. Racked by violence, gang rule and inequality, Honduras is one of the most unstable countries for a child to live in, especially for girls.

Compassion has partnered with the local church in Honduras for over 50 years, and our church partners have a deep understanding of the unique needs and assets of their communities.

Watch the video update below from our church partners in Honduras to learn more.

READ MOREkeyboard_arrow_down READ LESSkeyboard_arrow_upThank you for praying for staff, churches, children and families in Honduras we serve.

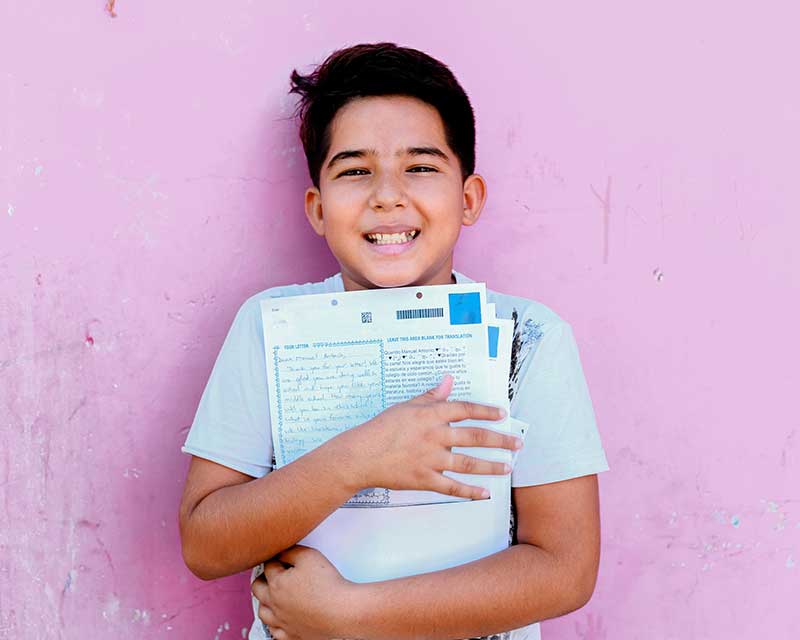

More than 250 children living in poverty have witnessed a powerful holistic transformation since their local Compassion centre opened its doors. Now, the lives of a new generation are being transformed! Read more open_in_new

Compassion’s program is contextualised across countries and communities, as well as age groups.

Compassion assisted children in Honduras typically attend program activities at their local child development centre after school. Here is an example of what a typical program day looks like for children in Honduras.

Devotional time - Children are taught to pray.

Spiritual lessons - Children sing songs and learn Bible stories.

Break and snack time - Children can play in a safe environment and develop friendships.

Social-emotional lessons - Children learn conflict resolution skills and how to develop healthy self-esteem and a godly character. Children often come from challenging home environments and are taught social and personal skills.

Lunch and social time - The majority of children do not have adequate nutrition in their homes and schools do not provide meals. Compassion centres at the local church aim to provide children with extra nutrition each time they attend the centre. Children experiencing malnutrition often receive extra food rations. Snacks usually consist of fruit, cereal and milk. Meals often comprise meat, cereals, vegetables and fruit.

Health lessons - Children learn practical health and hygiene tips.

Letter writing and career planning - Older children work with local staff to identify their strengths and interests and set goals for their future.

In addition, children are invited to participate in sporting tournaments, retreats, camps and educational visits. Older students are offered a variety of vocational skills workshops, such as welding, beauty, sports, baking, music, and computing. Parents and caregivers are offered parenting classes.

of people live in extreme poverty

of babies do not reach their first birthday

of girls aged 13 to 17 miss school due to experiencing physical violence

Honduras is rich with abundant wildlife and spectacular scenery, including one of the largest coral reefs in the world. Local families are tight-knit and passionate about soccer. Similar to other Latin American countries, extended family often live in the same house together and help one another.

Located in the corridor from South America to Mexico and the United States, Honduras is a transit country for everything from illicit drugs to human trafficking and mass migration.

Honduras’ history since Spanish colonisation in the 16th century is marked by military coups and counter-coups. Racked by violence and corruption, gang rule and inequality, it is one of the most unstable countries in a volatile region, with recent widespread drought creating further hardship for locals and leading to ever-increasing numbers travelling across borders—most headed north for Mexico and the United States.

Honduras has the second-highest extreme poverty rate in Latin America and the Caribbean, after Haiti. The country is also afflicted by one of the worst rates of inequality in the world, with a stark division between rich and poor.

Remittances (money sent home by expatriates) make up a significant part of the nation’s economy and many families are dependent on this source of income. Small-scale farming, the backbone of the nation’s agricultural economy, is collapsing; many rural communities are no longer able to sustain themselves due to drought and changing rainfall patterns.

Meanwhile, Honduran children living in poverty face many challenges, with malnutrition and insecurity foremost among them. They are particularly vulnerable to the threat posed by gang activity, with many boys coerced into joining and girls threatened with rape and forced labour. As meeting their basic needs becomes more difficult, some see gang life as the only alternative to starving or risking their lives on the road to the United States border.

Yet local churches across the country are working hard to nurture and protect these vulnerable children, to ensure they have the safety and space to grow and develop and experience the unfailing love of God.

READ MOREkeyboard_arrow_down READ LESSkeyboard_arrow_upWhen his mother collapsed at home in Honduras, Manuel's faith was stretched like never before. But the critical moment was yet to come for this Compassion sponsored boy... Read more

It can be disappointing if your sponsored child hasn’t responded to your questions or even mentioned the letter you sent them. Here’s why this could be happening, plus handy tips to prevent it. .. Read more

FGM, period poverty, child marriage, trafficking and disrupted education—these are real issues that girls living in poverty contend with every day. The challenges are immense, but they are not insurmountable... Read more